A Tour of St. George’s Anglican Church

by Bree Bergen

Winnipeg Architecture Foundation

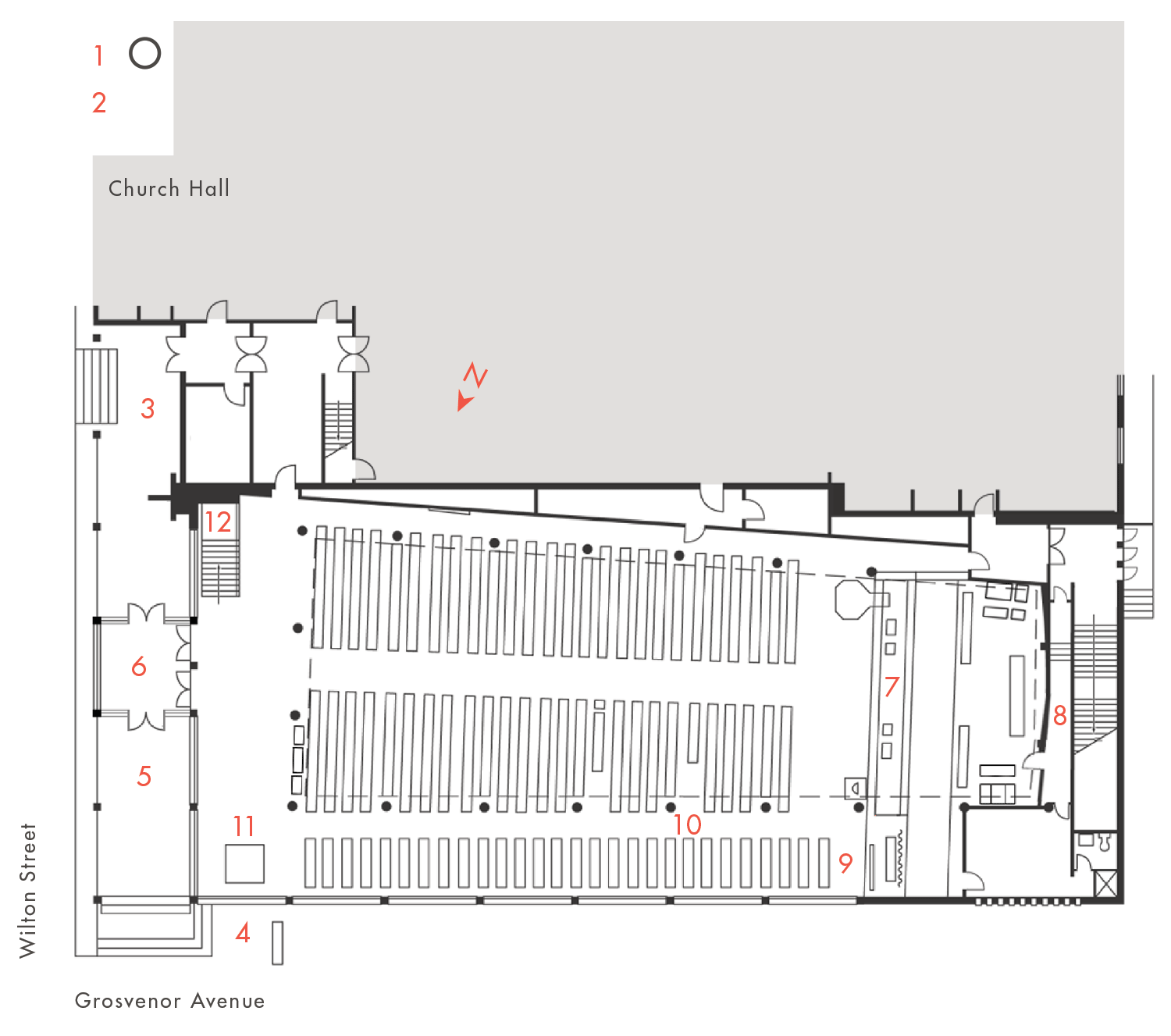

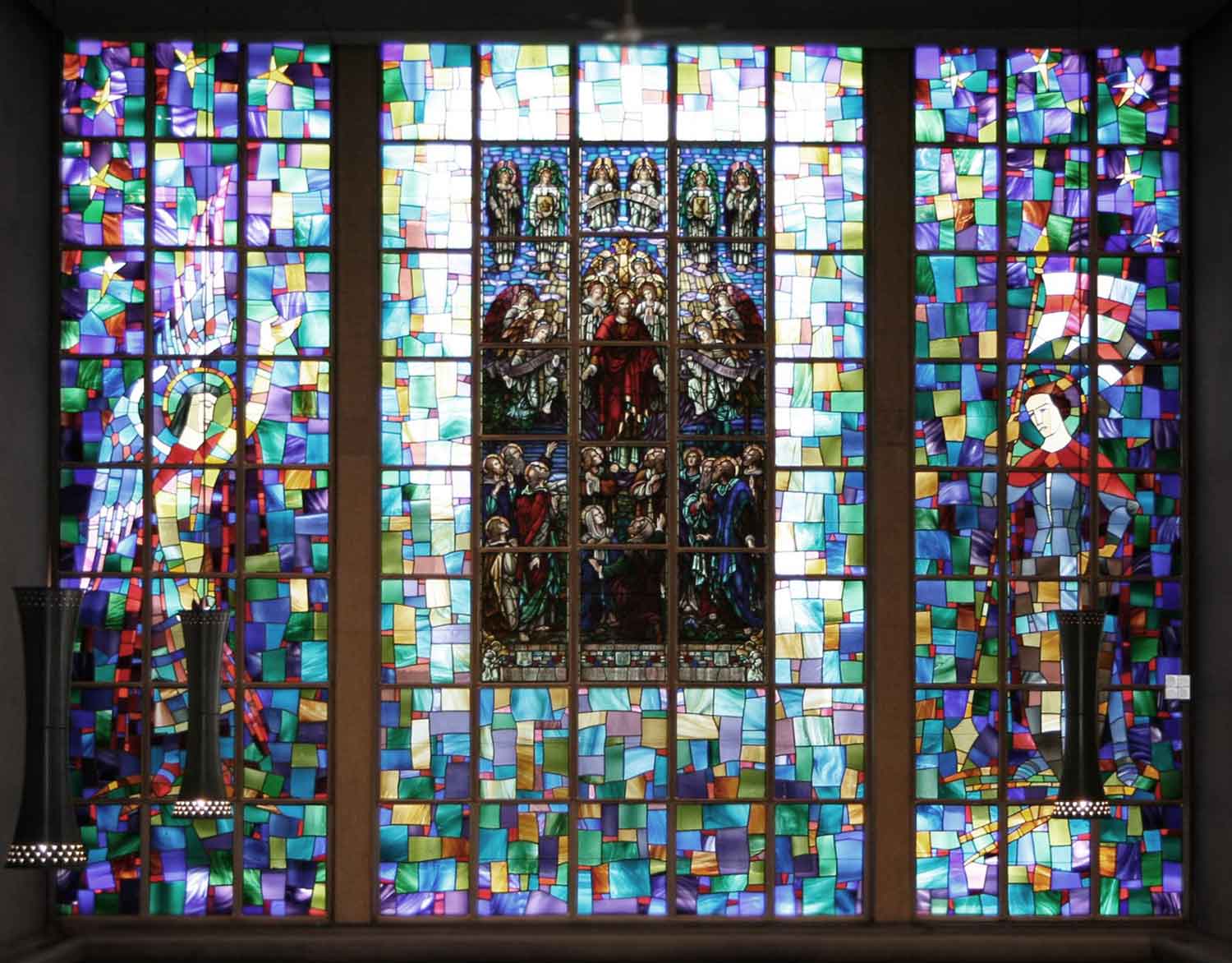

Tour of St. George's Anglican Church

(beginning with an introduction and history)

1

Wilton Street Elevation—Introduction & History of St. George’s Anglican Church

168 Wilton Street

| 1955–57 | Green Blankstein Russell and Associates |

St. George’s is the third Anglican Church to be constructed at the south eastern corner of Wilton Street and Grosvenor Avenues, in the residential neighborhood of Crescentwood. Construction was completed in 1957, marked by a corner stone laying ceremony on November twenty-fourth of the same year.1 The first service in the new edifice was held on Palm Sunday, March 31, 1958.

The original congregation of St. George’s held their first service in a rented and retrofitted school house, situated on the grounds of the Old Central (Victoria) School, on November 24, 1883. The following year, a purpose-built structure was constructed on the corner of William Avenue and Lydia Street, within what was then Winnipeg’s warehouse district. At this time, Winnipeg was Canada’s third largest city and expanding rapidly. In 1915 the church, eyeing an opportunity to establish itself within a new residential development south of the Assiniboine River, purchased the current site. That same year witnessed construction of a small prairie church, which was completed the following year, in 1916. In 1927 and 1946 successively, larger structures replaced the earlier buildings, as the community of Crescentwood and the St. George’s congregation continued to expand.

In 1945 and 1946, immediately following the end of the Second World War, an office wing was built, quickly followed by a church hall designed by John Nelson Semmens. The hall remains on the southern portion of the site, and shares its north facing wall with the current church. This hall serves to clearly illustrate the shift from historical derivation to modern innovation that came to typify the Anglican churches that were designed and built in the post-war period. In character the hall is Gothic Revival, a style typified by pointed arched fenestration, decorative detailing, an overall sense of verticality and masonry construction.2

Attitudinal changes within the Anglican Church of Canada (ACC), in the post-war years, paralleled advancements in engineering and the architectural thinking about church architecture. A celebration of innovation and a desire to meet the perceived needs of the public replaced an unquestioning deference to, and refinement of, established stylistic precedents. Traditional layouts and materials, like stone and timber, were traded for simple geometric forms and industrial materials such as steel, concrete, and plastic. Historically, High Anglican church architecture reflected Gothic Revivalism, with a single processional entrance and a layout emphasizing a division between the clergy and congregation, reinforced in the plan and interior layout of the church and nave. Modern Anglican churches, by contrast, often aim to create an active feeling of inclusion.

Formed at the January 12th meeting of the Vestry in 1955, the Building Committee, which included, Rev. F. George Gartrell, Joan Harland, A. R. Little, T. H. Kirby, H. E. Swift, and Professor R. Glover, established the mandate “to search for ideas regarding the design and architecture for a new church.”3 The Building Committee met weekly, for an approximate total of twenty meetings. Decisions for the design and plan of the church were guided by this committee, with member, British-born Joan Harland, taking a direct and leading influence on the development of the design. Joan is a long standing member of the St. George’s congregation, and of the Crescentwood community. Five firms were interviewed, including Prain and Ward, Semmens and Allison, Green Blankstein Russell and Associates, and Moody Moore and Partners.4 The following points were outlined and presented to the prospective firms during the interview process (paraphrased):

- the new structure must conform acceptably with the existing Parish Hall;

- the new church should be reoriented so that its primary entrance is on Wilton Street;

- because of the existing flat roof on the Parish Hall, a flat roof on the church (with internal drainage) would be the most practical and would be ”acceptable from the point of view of design;”

- a tower or spire should be included to “accent” the flat roofed structure;

- the existing church furniture will be reused, exempting the altar, which may be redesigned or placed next to the outside row of pews on the Grosvenor Avenue side of the nave. Moving it here would allow the roof to be lower on this side and consequently narrow the roof span to approximately 30’, accenting the height and sense of verticality within the nave;

- the finish of the ceiling is of utmost importance;

- design must include both sacristy and vestry;

- the organ and organ chamber must be considered as an integral part of the design and building;

- a gallery would be welcomed, but is not necessary; the existing stained glass should be recomposed to produce a generous window over the altar.

Following the interviews, on May 2 1955, the committee recommended the architectural firm Green Blankstein Russell and Associates (GBR) to design the new church, with Leslie Russell acting as Lead Architect. In a statement recorded during the Conference on Church Architecture held at the University of Manitoba’s School of Architecture in February of 1964, Russell observed,

“It is obvious that while the church may be grand, while it may be a great Cathedral, it should not be ostentatious, it should not be seeking self-glorification. It is obvious that the church should not be built according to a fashion, A-frames this year, parabolic arches next. It may be that the church must be built of simple, humble materials, but they should be the best materials of their kind, and the workmanship should be the very best of which the workers are capable.”5

The Building Committee and Russell enjoyed a productive and positive working relationship. This was, in part, due to Harland’s preexisting knowledge of the firm’s work. Russell and GBR operated their firm with a progressively collaborative attitude. Speaking again at the Conference for Church Architecture held at the University of Manitoba, Russell stated, “I don’t think that a church should be designed by an architect working within an ivory tower. Rather, the design should result from the working together of the architect with a devoted building committee.”6

The contract for construction went to tender and bids were received from Bockstael, Claydon, Commonwealth Construction, Swanson, Wallace and Akins, Peter Leitch and Fraser, and H.J. Bird. The contract was awarded to the lowest bidder, Winnipeg-based construction company H.J. Bird, who was an Anglican himself. Cost of construction was approximately $450,000. The architect’s professional fees were contracted at six percent of the total cost of construction, or approximately $21,000.00. Fifteen years later, in 1973, the church was both consecrated and the mortgage completed.

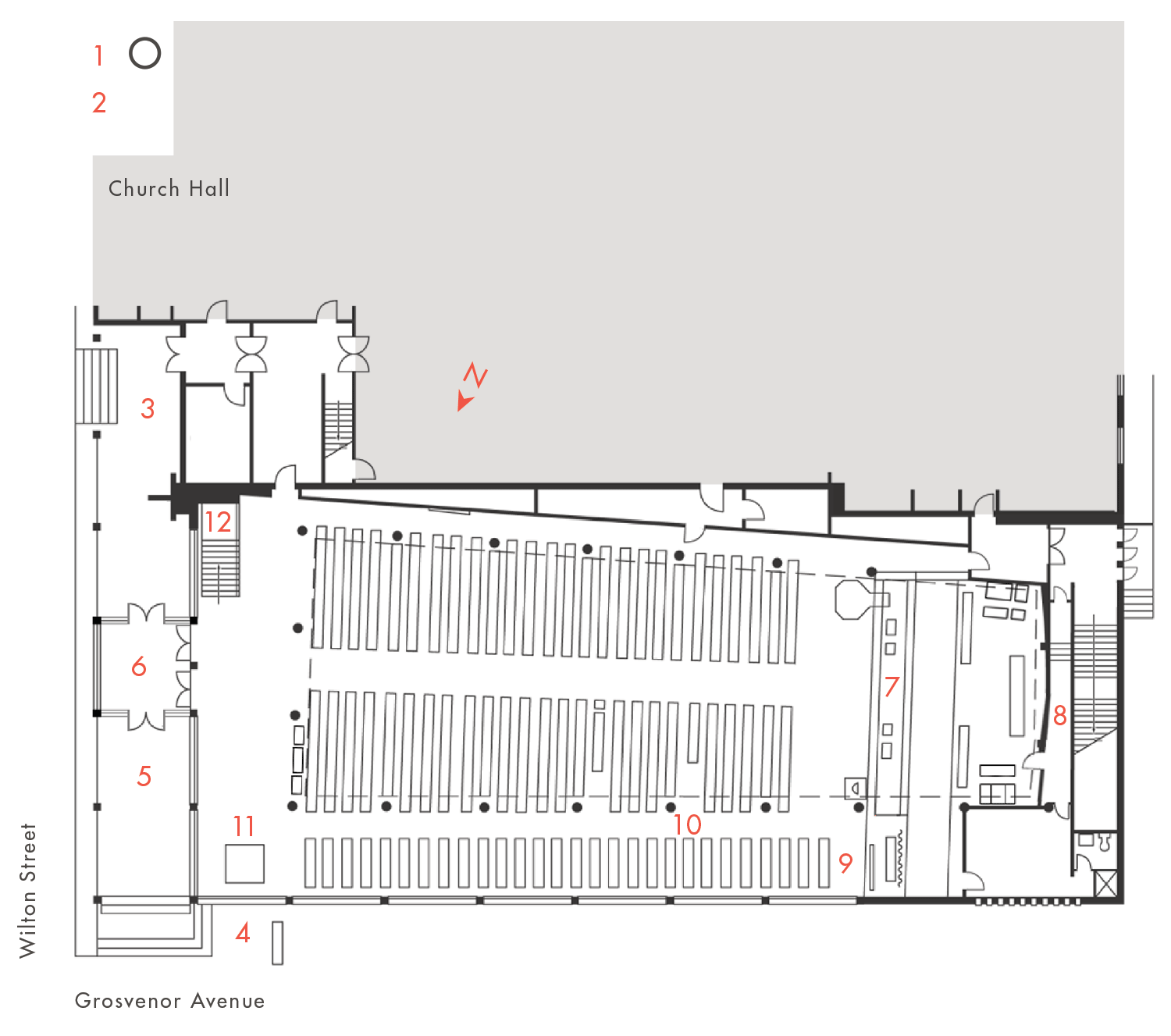

2

Bell Tower

168 Wilton Street

The last item considered by the architect was the one hundred and thirty-two-foot bell tower. The tower, cruciform in plan with arms of equal length, was designed to have presence without visually competing with the preexisting fire hall tower on Wilton Street. Construction was of reinforced concrete, cast on site using plywood formwork. Joints between pours were notched, and the edges chamfered. The tower stands in elegant, slim contrast to traditional Gothic-inspired bell towers, which are larger to accommodate bells and a requisite stairway. Russell added a narrow pipe-lined raceway in the centre of the concrete tower to provide power to a modestly sized electronic clapper, constructed by Dominion Bronze and Iron Limited based in Winnipeg’s west end. The clapper was installed prior to the last concrete pour. Generally an iconographically understated church, the tower’s ten-foot cross at its peak is one of only three that appear in both the interior and exterior of St. George’s Church.

3

Wilton Street Elevation

168 Wilton Street

When approaching St. George’s Anglican Church from the east, the elevation is marked by a large, yet simple cross, framed in a rectangular glazed opening in an extruded aluminum frame. Supporting the covered porch below, the vertical columns visually extend the lines of the cross to the ground, symbolically uniting the people with the divine. These features reflect Russell’s remarks that:

“When we build a church we are doing something more than building a building. We must look at this process of building in a more philosophical way. We are seeking to create an environment for worship; we are seeking to image the thoughts, the words, the actions of man in his relationship to God. To some perhaps the environment is not important, but, to many who go to church seeking a closer relationship with God, it is. The environment surely can be measured by its success or failure in helping the worshipper in his search for God.”1

4

Grosvenor Street Elevation

168 Wilton Street

The Grosvenor Avenue elevation is similar in character to the Wilton Street façade, asserting a modest horizontal character typical in modernist dwellings and prairie influenced architecture. The elevation is similarly veneered in locally quarried, four-inch thick, smooth face, Tyndall stone.

The design illustrates sensitivity toward the physical characteristics of the site and neighborhood. Russell took care to scale St. George’s height to the surrounding three-story, wood-frame houses of Crescentwood. “While the church may be grand,” he wrote, “while it may be a great Cathedral, it should not be ostentatious. It should not be seeking self-glorification.” His design also embodies a distinctly modernist concern for material authenticity and workmanship:

“In seeking to create this environment man should avoid dragging in the faults to which he is prone. It is dishonest, for example, to use imitations, plaster made to look like stone, or wood made to look like marble…. It may be that the church must be built of simple, humble materials, but they should be the best materials of their kind, and the workmanship should be the very best of which the workers are capable.”1

Historically, a church is centered on its site, allowing for a processional entrance along the centred axis. This grand stair would serve to function as the predominant feature of the structure’s front elevation. In contrast, St. George’s sits off-centre on the site and eschews the elaborate ceremonial stair for a more human-scale, welcoming set of entrances. The dual set of entries, accessed via both Grosvenor and Wilton Avenues further reinforces the church’s overall neighbourly and hospitable character.

In a letter to Rev. Gartrell on June 27, 1958, Leslie Russell requested that the two pyramidal cedars planted in the planting boxes along the Wilton Street elevation following the completion of construction, by the congregation, be removed and instead, “replaced with a low planting of uniform height.”2 Russell explains that the cedars are “especially distressing” because they had been placed directly in front of two of the columns and thus mask the lower portion of the structure.

5

Doors

168 Wilton Street

Sculptor Cecil Richards, then professor in the School of Art at the University of Manitoba, was commissioned to carve oak relief panels for the 10-foot high entrance doors. At Gartrell’s request, the panels illustrate important biblical narratives.1 Consolidating the imagery here removes it from where it would be placed in a historic church, in the narthex or nave, and instead allows for a visually clear, ornamented interior. The shape of the handles is repeated in the interior, in the pendant lighting. As Richards described it,

“The first of two pairs of carved oak entrance doors. The subject matter was chosen by the minister of the church and a committee. I made several sketches in clay before commencing carving in wood. All panels are carved in oak, about an inch in relief. After the decisions on subject matter I was given complete freedom to style. On the pair of doors illustrated the four panels represent the Four Gospels and the second four early Christian Saints. The second pair of doors, yet to be completed (in 1960), will carry four panels representing the Four Churchmen of the Reformation, and four panels on a subject yet to be chosen.”2

6

Narthex

168 Wilton Street

The narthex is an uncluttered, light-filled space, perpendicularly offset from the nave. The interior’s open plan is possible because of post-war structural advancements, including the use of structural steel and reinforced concrete. The strength provided by these new materials allowed for the beams to be longer while carrying additional load, resulting in increased spans between columns. Further, the relative strength of steel and concrete made flat roofs possible, providing modern buildings like St. George’s with a distinctive visual simplicity, linear character, and rectilinear massing.

7

Nave & Chancel

168 Wilton Street

The ceiling in the nave is thirty-five-feet high and one hundred and twenty-eight-feet long. Interior walls are finished in lathe and plaster. Joan Harland headed the committee responsible for overseeing the design of St. George’s interior. The furnishings are made from natural walnut, sourced in part from Ontario’s Valley City Manufacturing Company.1

In modernist churches, the sanctuary is often used to mean both the chancel and nave because the two are not architecturally distinct. However, St. George’s is divided by an extended stair, with multiple risers. The chancel walls are finished in alternating oak battens, backed by plywood. The altar is free standing, set away from the rear wall.2

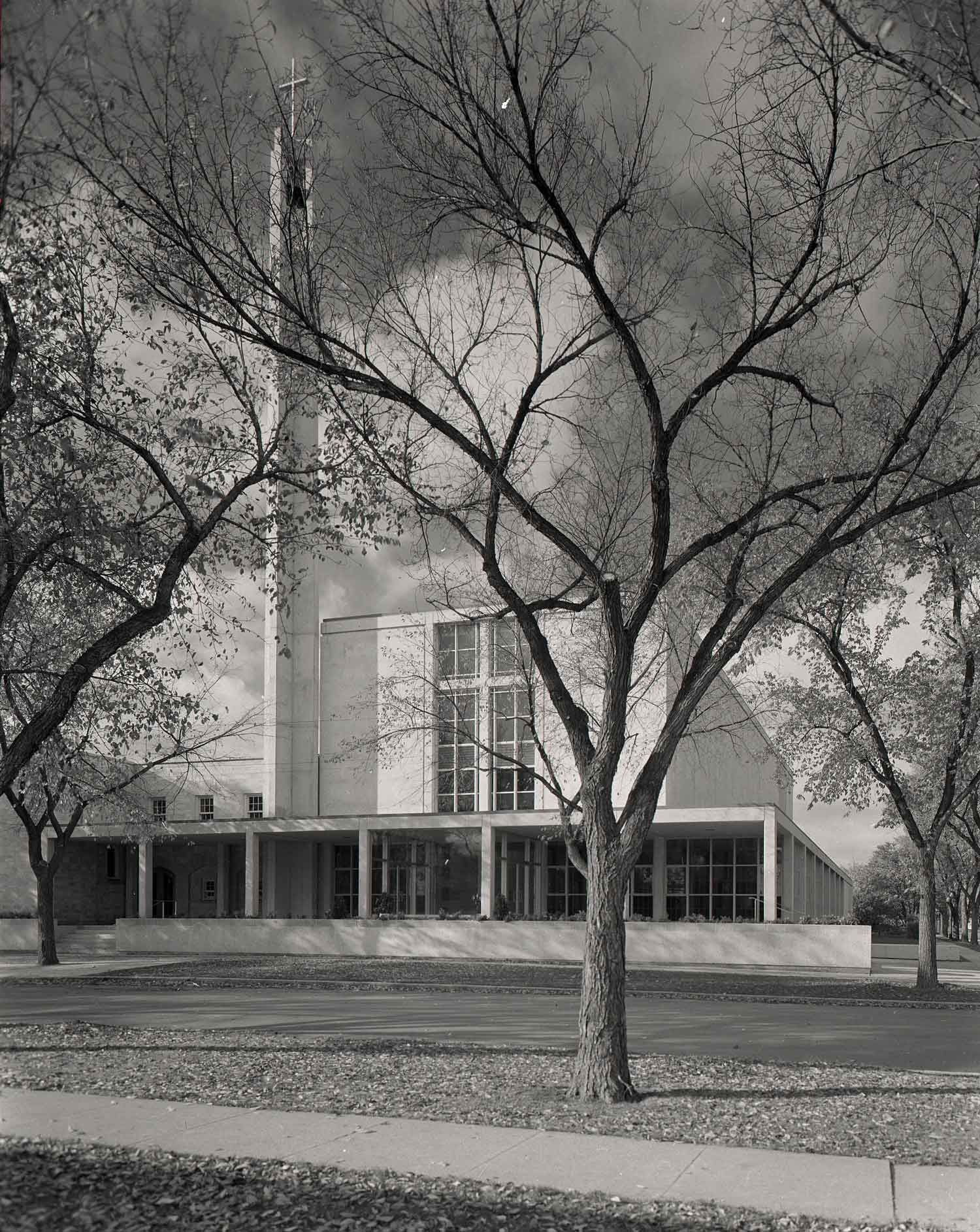

8

Stained Glass (West)

168 Wilton Street

The west wall includes a twenty-four by thirty-two foot abstracted window by Winnipeg sculptor and stained glass artist Leo Mol. Implanted at the centre of Mol’s design is a six-by eight-foot-window from the previous church depicting the Ascension. Two additional panels on either side of the central panel depict Saints Michael (south) and George (to the north). Viewed together the two windows capture the shift from traditional church design and character to the decidedly Modern sensibility evident in the luminous, graphic window by Mol.

9

Stained Glass (North)

168 Wilton Street

Operable stained glass windows on the northern side aisle, also by Leo Mol, are interspersed with over thirty Christian symbols, including a fish, an open book, and a lantern. In contrast to the bright glass on the western elevation, these north facing windows provide a softer, restricted light, and privacy from the exterior traffic.1

10

Columns

168 Wilton Street

Reinforced concrete columns, at fourteen-foot-intervals, line the centre and northern side aisles and support the elevated roof within the nave. The Design Committee, with the recommendation of artist and University of Manitoba sculpture professor George Swinton, chose the colours of the mosaic tile to reference the stained glass in the west-facing window: red, green, yellow, pink, brown, and black accent a largely blue ground. The architect contracted an Italian firm for the glass tile; however, sourcing the tile fell to Swinton. On a trip to Italy, he returned with bags of loose tile, which volunteers from the congregation then sorted and divided by colour. Over several subsequent weekends, volunteers arranged the tile into one-foot square plaster molds.

Joan Harland, in an interview with the Winnipeg Architecture Foundation, stated that there was additional work following the completion of the tile layout. A group of teenage volunteers had formed crosses from the small mosaic pieces and had interspersed them throughout the one-foot-square panels. As the tile design was intended to appear completely random, and only one cross was to appear in the sanctuary, over the chancel, the crosses were removed and the tiles redistributed.

11

Baptistry

168 Wilton Street

The baptistry, where baptism is conducted, is a stand and water basin that is usually integrated, but occasionally composed of two separate pieces. The baptistry may be permanent or moveable and is positioned either in the front of the congregation or just inside the entry. At St. George’s, the baptistry is a moveable structure from the 1916 church, and sits atop a modern Tyndall stone plinth.

12

Choir Loft

168 Wilton Street

St. George’s choir was reoriented in the new building. Instead of appearing at the front of the church, it was placed behind the congregation and elevated above the narthex. There were practical reasons for this decision: the chancel was less visually cluttered; a greater sense of flow was created for the congregation during the Eucharist; and, the church service was freed from the distractions of shuffling paper and the massive organ. This move intended to allow greater focus on the service proper. Joan Harland, in particular, lent support for the choir’s placement; she had seen a similarly oriented choir in Minneapolis, Minnesota at Christ Church Lutheran (1949) designed by architectural firm Saarinen and Saarinen.1

13

Additional Work

168 Wilton Street

Additional work at the Church included the addition of a crawl space below the Hall; May 1980 structural repairs to Hall and Church; and underpinning of the Hall in June 1984.

Glossary

Baptistry

When baptism is administered by pouring, the baptistry is a stand and water basin (sometimes integrated, occasionally of two pieces). The Baptistry may be permanent or moveable, and is often in the front of the congregation or just inside the entry.

Gothic architecture

An architectural style that flourished during the Medieval period, originating in 12th century Europe. Evolving from Romanesque-style architecture, and later replaced by Renaissance architecture, it is typified by the pointed arch, limited fenestration, vaulting, compression structures, masonry construction, and an overwhelming sense of verticality.

nave

The architectural term for the place where the congregation sits. It stands in opposition to the front portion of the church where the service is led. In churches with an open floor plan, the term ‘sanctuary’ is often used to mean both chancel and nave because the two are not architecturally distinct. However, St. George’s is divided by an extended stair, with two risers.

narthex

A traditional term for what is otherwise the foyer of the church.

sacristy

The sacristy is the room or closet in which communion equipment, linen, and supplies are kept.

Biographies

Joan Harland

(b. 1914)

Joan Harland was born in Leeds, England on 10 December 1914, shortly after the start of World War One. Her parents lived at 1120 Grosvenor Avenue in Winnipeg, adjacent to the present site of St. George’s Anglican Church. After attending nearby St. Mary’s Academy, Harland took her degree in Architecture at the University of Manitoba, graduating in 1938, earning the Gold Medal for her class. Following her graduation she found work with the famous Winnipeg office of Brigden’s catalogue and art company. Shortly thereafter — in the academic year 1939–40 — the young designer started with the School of Architecture as the first instructor in interior decorating classes at the university. Here she joined with the only two other instructors, Dean Milton Osborne and Professor John A. Russell, and lectured on a variety of subjects, forming the basis of the first specialized program of its kind in Canada.

Harland attended Columbia University for the summers of 1945–47, ultimately obtaining a Masters of Fine Arts degree. Harland continued to build the department and played an integral role in developing the Department of Interior Decorating within the School of Architecture. With the enthusiastic support of Dean Russell, Harland became first the Chairman of the Department and later, Department Head. Harland also left her mark in building the Interior Designers Educators Council of Canada (IDEC) as a separate entity from the more conservative American Interior Decorators Council. She also served as president of the Manitoba Institute of Interior Designers. Covering a broad variety of study topics, Harland lectured and lead as Department Head until she stepped down in 1967.

Photo: Joan Harland (University of Manitoba Graduation), 1938

George Swinton

(1917–2002)

George Swinton was born and grew up in Vienna, Austria. In 1939 he escaped Nazi-occupied Austria and immigrated to Canada where he enlisted in the army and served overseas until 1945. After the war he became interested in painting as a means of readjusting to civilian life. He went on to study art at McGill, the Montreal School of Art and Design, and the Art Students League in New York. Swinton became the curator of the Saskatoon Art Centre from 1947–1949. He was an instructor at Smith College from 1950–1953 and Artist-in-Residence at Queen’s University from 1953–1954. He taught painting at the University of Manitoba from 1954 to 1973, and helped to introduce modern art to Winnipeg in the early 1950s. He was a guiding force behind the Winnipeg Show at the WAG through the 1950s and 1960s and then moved to Ottawa where he taught art history at Carleton University until 1981. In addition to his teaching and studio practice, Swinton is credited for bringing Inuit art to a wide public notice with his landmark book Sculpture of the Eskimo, which was reprinted for the third time as Sculpture of the Inuit in 1999. He was the art critic for the Winnipeg Tribune from 1954–1958. He hosted the CBC television series “Art in Action” from 1959–1962. He was the recipient of many honours including the Centennial Medal in 1967, Member of the Order of Canada in 1979. His work is included in the collections of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Glenbow Museum, Mendel Art Gallery, Art Gallery of Hamilton, and the National Gallery of Canada, among others.

Photo: George Swinton (by unknown photographer), 1960s

Leo Mol

Leonid Molodizhanyn

(1915–2009)

Leo Mol was born in Ukraine in 1915. He studied at the Leningrad Academy of Arts and later continued his studies in Berlin and The Hague. In 1948 he and his wife, Margaret, came to Canada and made their home in Winnipeg. Mol carried out sculptural commissions of world figures such as Pope John Paul II, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and John Diefenbaker. Mol’s stained glass work includes the windows of St.George’s Anglican Church, Westworth United Church, St. Patrick’s Church as well as the exterior mosaic of Holy Trinity Cathedral on Main Street. He was a member of the Royal Canadian Academy and in 1989 was appointed an officer of the Order of Canada in recognition of his artistic contributions to his adopted country. The Leo Mol Sculpture Garden officially opened in Winnipeg’s Assiniboine Park in 1992. Since that time the garden has attracted visitors from the around the world and enriched the cultural life of Winnipeg.

Photo: Leo Mol (by unknown photographer), 1974

Clarence Cecil Richards

(1907–81)

Cecil Richards was born in Breage, Cornwall, England. In 1925, Richards immigrated to Canada, settling in Toronto. He studied sculpture and drawing at the Ontario College of Art (1927–31). Upon graduation, Richards established a studio in Toronto where he worked and taught sculpture until 1942. During the war, Richards served with the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps and studied overseas at the Guildford School of Technology. In 1945, following his discharge from the army, he entered the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan where he worked as an assistant to Carl Milles, a noted Swedish sculptor. In 1948 Richards taught at the Institute of Art at Flint, Michigan, later at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, at the University of British Columbia and at the University of Texas. Later, in 1952, he was appointed Associate Professor at the University of Manitoba where he established the Department of Sculpture and became its first Chairman. He taught at the University until his retirement in 1966 when he settled in Lakefield, Ontario. Commissions include, The Gathering in the foyer of the Winnipeg Convention Centre; doors for the Chapel of the Winnipeg General Hospital; an indoor fountain for the Middle-church Old Folk’s Home and the doors of St. George’s Anglican Church. Cecil Richards was a member of the Canadian Sculpture Society (1955) and an Associate of the Royal Canadian Academy. In 1971 a documentary on him was made by the NFB entitled A Quiet Wave (produced by George Pearson and Dorothy Courtois). Richards work is represented in the collection of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the Winnipeg Airport; Trent University, The Art Gallery of Ontario, and the National Gallery of Canada.

Photo: Clarence Cecil Richards (by Henry Kalen), 1960s

Bibliography

Archives

- Henry Kalen photographs. Henry Kalen Collection. University of Manitoba Archives.

- St. George’s Anglican Church Parish Archives. St. George’s Anglican Church, Winnipeg.

Books

- Benham, Mary. Once More Unto the Breach – St George’s Anglican Church. St. George’s Anglican Church, 1982.

- Graham, John W. Guide to the Architecture of Greater Winnipeg. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1960.

- Harland, Joan. Architecture, Interior and Exterior, St George’s Anglican Church. St. George’s Anglican Church. (available at St George’s Anglican Church)

- Harland, Joan. Ruth Stirk, eds. A Guide to the Parish Church of St. George. St. George’s Anglican Church, 1996.

- Keshavjee, Serena ed. Winnipeg Modern 1945–1975. University of Manitoba Press, 2002.

Newspapers and Periodicals

- Church Editor. “New Edifice For St George’s”. Winnipeg Free Press. February 9, 1957.

- Church Editor. “Eighth Home Is Its Finest”. Winnipeg Free Press. April 12, 1958.

- “Perpendicular Projections to the Horizontal Prairie.” RAIC Journal (April 1960): 132.

- “Carved Entrance Doors, St. George’s Church”. RAIC Journal (April 1960): 143.

- University of Manitoba. Proceedings for the Conference on Church Architecture for the Prairie Region, at the University of Manitoba, (February, 1964).

Websites

- St. George's Anglican Church.

- Archiseek.